Compassion in World Farming Research Manager Catherine Jadav dissects some of the dangers of the factory farming industry, discussing the spread of zoonotic diseases that can cause future pandemics

First published October 2021 in Open Access Government.

Factory farming, developed in the U.S. during the twentieth century, was introduced to Europe after the Second World War. Often referred to as ‘intensive farming’, it involves the rearing of animals indoors and on an industrial scale: imagine tens of thousands of meat chickens packed tightly into one shed, egg-laying hens crammed into cages with less space than an A4 sheet of paper each, or mother pigs immobilised in metal crates that prevent them even turning around. These are just a few examples, and, sadly, in the few decades since this type of ‘farming’ was introduced, it has become the norm – so much so that many now term it ‘conventional farming.’ Worldwide, the majority of the 88 billion animals used for food each year are factory farmed; in the UK, the proportion of animals that are factory farmed is approximately 80%.

One result of factory farming is an abundance of relatively cheap meat, eggs, and dairy on supermarket shelves and in food outlets. However, this type of animal agriculture also has many far less desirable effects, including an increased risk of zoonotic disease, antibiotic resistance in human medicine, and the danger of creating future pandemics.

The highly unnatural conditions of a factory farm – where up to tens of thousands of animals are crowded together indoors – provide the perfect environment for the rapid spread of viruses and bacteria to many animals. The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the importance of space, fresh air, and UV rays in limiting the spread of disease; such principles apply equally in animal farming. Moreover, as we have seen with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, as a virus infects more people, it can mutate, giving rise to new, and often more dangerous, strains. Similarly, as a pathogen spreads like wildfire through thousands of new animal hosts on a factory farm, there is a much greater chance of it mutating, risking the emergence of strains that are not only more harmful, but which have zoonotic potential – i.e., the ability to infect humans.

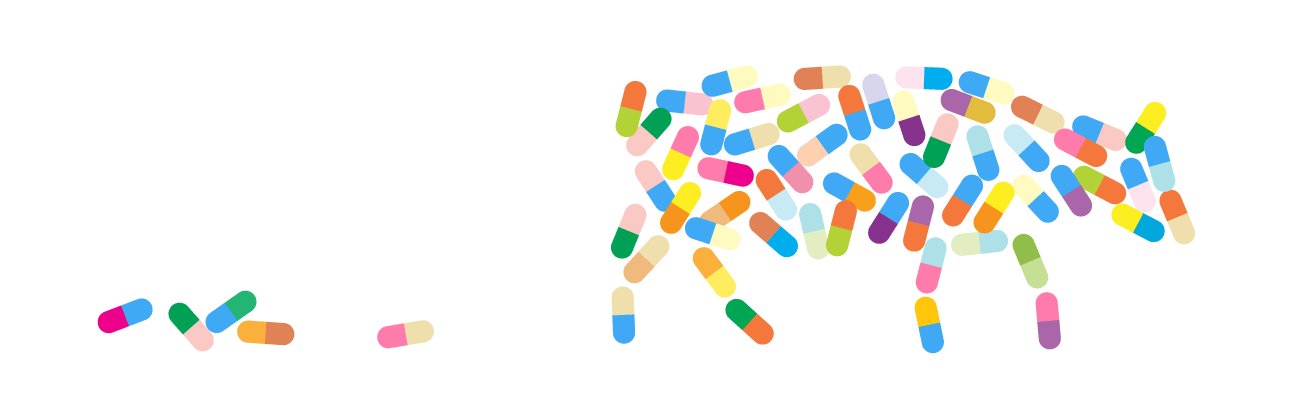

It has happened before – the last global pandemic, swine flu, was caused by a virus that spread in farmed pigs and developed the ability to infect humans. It started in Mexico, just five miles from a major concentration of intensive pig farms and went on to kill up to half a million people worldwide.

A 2020 study of 2,500 European pig holdings discovered the year-round presence of several major swine flu viruses on more than half of the farms examined. The authors conclude that European pig populations form reservoirs for emerging influenza A virus strains that have both zoonotic and pre-pandemic potential.

It is well recognised that the intensive farming of livestock poses a major pandemic risk. The report Preventing the Next Pandemic (UN Environment Programme and the International Livestock Research Institute, 2020) identifies unsustainable agricultural intensification and increasing demand for animal protein as major drivers of zoonotic disease emergence. Likewise, the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services states: ‘The underlying causes of pandemics include … land-use change, agricultural expansion and intensification.’

In an attempt to compensate for the disease-promoting conditions of factory farms, the sector has come to rely heavily on the prophylactic use of antibiotics. This involves antibiotics being given routinely to all animals, via feed or water, to prevent infection, which would otherwise be inevitable in such conditions. An estimated 66% of all antibiotics employed worldwide are used in livestock. As such, livestock farming is a major driver of antimicrobial resistance in humans, a problem that could cause 10 million deaths per year by 2050. The major culprit here is the intensive farming sector; a recent report by the European Medicines Agency states that the use of antimicrobials ‘in extensive production systems is generally relatively low’. In the Netherlands, where a significant proportion of meat chickens are of healthier, slower-growing breeds, industry data shows that these are at least three times less likely to need antibiotic treatment than intensively farmed, fast-growing breeds. In the UK, a 2021 study found that overall antibiotic use on Soil Association-certified organic farms was four times lower than the national average. Similarly, a recent study concerning Danish pig farms found, on average, up to 15 times lower antibiotic use on organic farms than on intensive farms.

Less-intensive livestock farming systems, including organic, agroecological, and regenerative approaches, place emphasis not on maximising productivity at any cost, but on providing more natural environments that promote good health, low stress, strong natural immunity and low incidence of disease. The abundance of clear evidence and experience demonstrate that an urgent mainstream shift to these healthier and more sustainable farming systems is essential if we are to minimise further antimicrobial resistance and reduce the risk of further zoonotic disease and the potential for future pandemics.